Forsaking Black Resistance: The Role of Black History in Decolonization

This is the last blog in a set of three commissioned blogs from Professor Tommy J. Curry. Tommy is a Professor in Philosophy at the University of Edinburgh. These blogs follow on from Tommy’s lecture series from June 2022 and January 2023. The blogs will assess the challenges before museum educators, curators, and theorists in their quest to decolonise the museum. Read the last blog, Decolonizing the Ethnological Epoch of the Scottish Enlightenment.

The role of Black History in Decolonization

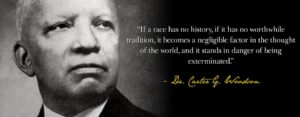

The Negro has no desire to be everything the white man is or to do everything he does…The Negro is not a white man with a black skin. If the blacks were suddenly transformed in spirit into white people, the racial conflict which would ensue would give rise to a state of anarchy which would not only drench the soil with blood but would result in the extermination of a large portion of mankind” (Carter G. Woodson, The Appeal, 1921).

The United Kingdom has mobilized history, philosophy, religion, economics, politics, and science to justify the inferiority of African and African descended peoples. For over two centuries, violence, genocide, and colonialism were imposed on Black peoples to enrich white Europeans and impoverish the darker world. Decolonization acknowledges the consequences of Europe racist logics upon human knowledge and history. History, or what is often understood as a cataloging of events from the past, is a contested ground. The history of white civilization is also a history of savage violence and brutality against Africans, Asians, and Indigenous peoples. This barbarism of Europe is presented as a triumphant historical narrative where the deaths of Black peoples and the eradication of Black achievements are testaments to the advance of Anglo-Saxon superiority.

Many scholars and institutions have undertaken the decolonization of history as an attempt to produce a more accurate and truer version of historical events and epochs than those produced by white Scottish institutions and intellectuals of the past. It has only recently been admitted that Scottish history has had ties to slavery and colonialism and has played a substantial role in birthing theories of racial inferiority. The myth of white racial superiority was part of the heritage of Great Britain’s national legacy.

The Edinburgh Slavery and Colonialism Legacy Review, for instance, presents the overlooked and denied histories of national monuments and institutions that benefited from slavery and colonialism. The efforts to expose the historical legacies of slavery and colonialism is a necessary first step in dealing with contemporary forms of racism, but ultimately an incomplete one. The history of anti-Blackness is not only an erasure of the harms and injury caused by European colonialism, but the eradication of the genius and accomplishments of African, Asian, and Indigenous peoples the world over.

To say that history is Eurocentric is not only to say that the written records of history focus almost exclusively on the triumphs and events of white peoples, but to also say that the ideas, writings, civilizations, and resistances of Black peoples against white imperialism are ignored and deliberately erased from the annals of history. If an oppressed race is never taught that there is a history in which their people strove for higher ideals—freedom, nation, equality, and humanity—the descendants of those oppressed peoples remain dependent upon the ideas of their oppressors for truth and their future aspirations. The history of white racism and violence should be studied, acknowledged, and understood, but it is the resistance, the endurance, and refusal of Blacks to be defined by white supremacism that deserve much more focus in our efforts to decolonize.

Black History in the United States was always thought of as the foundation upon which racial consciousness and the development of Black culture grows. From enslavement to the mid-twentieth century, Black American men and women embraced a nationalist form of politics emphasizing the self-determination of Black peoples. Inspired by the Haytien Revolution (August 21, 1791-January 1, 1804), 19th and 20th century Blacks used Black revolutions, slave uprisings, and the ongoing struggles against white supremacy as evidence that the supposed inferiority of Black peoples was based in the racist polices of America, not nature. Black scholars such as James McCune Smith, Frederick Douglass, John Edward Bruce, Arthuro Schomburg, Antenor Firmin, W.E.B. DuBois, Ellen Irene Diggs, John Henrik Clark, and Drucilla Dunjee Houston, wrote of the great accomplishments and revolts of African peoples against European imperial endeavors. Resistance became entrusted to Black schools of thought such as the American Negro Academy (founded in 1897), or the Negro Society for Historical Research (founded in 1911).

Carter G. Woodson was one of the most prominent voices for a Black History. He understood that the denial of Black resistance to white domination throughout history inculcated submission and passivity in the Black race. Ignoring the history of Black resistance is to transform the myth of white racial superiority into a psychology of Black racial inferiority. In The Miseducation of the Negro (1933), Woodson explains

No systematic effort toward change has been possible, for, taught the same economics, history, philosophy, literature, and religion which have established the present code of morals, the Negro’s mind has been brought under the control of his oppressor. The problem of holding the Negro down, therefore, is easily solved. When you control a man’s thinking you do not have to worry about his actions. You do not have to tell him not to stand here or go yonder. He will find his ”proper place” and will stay in it. You do not need to send him to the back door. He will go without being told. In fact, if there is no back door, he will cut one for his special benefit. His education makes it necessary (Preface).

At the height of the Civil Rights movement, Black activists and intellectuals started the museum movement to make the accomplishments of the Black race more public (Burns 2013). Black museums were created throughout the 1960s. The DuSable Museum of African American History (1961), the International Afro-American Museum in Detroit (1965), the Anacostia Museum in Washington D.C. (1967), and the African American Museum of Philadelphia (1976) rose to educate a Black public still fighting against the denigration of the Black race.

The inaugural meeting of the International Afro-American Museum (IAM) in 1965 (pictured above) was a continuation of this resistance tradition among Black Americans. The historian Mabel Wilson argues Black museums like the IAM created counter-publics challenging the dominant white historical myths of Black inferiority. “The establishment of new black museums allowed for the long-term presentation of ideas of black pride and self-improvement and for the collection of artifacts of black heritage,” writes Wilson (2012).

Decolonization requires an earnest commitment to inquiry and the courage to look beyond the history produced by white Europe to find what may be the very first demonstration of human knowledge and theories of freedom known to civilization.

Recommended Readings

Andrea Burns, From Storefront to Monument: Tracing the Public History of the Black Museum Movement (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2013).

Mabel Wilson, Negro Building: Black Americans in the World of Fairs and Museums (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012).

Carter G. Woodson, The Appeal (Washington, DC: ASALH Press, 1921).

Carter G. Woodson, The Miseducation of the Negro (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 1933).